Writers and dissidents of the 60s (Sixtiers) are well known to Ukrainians – during the Khrushchev Thaw, those groups protested against the totalitarian Soviet regime and wanted to divert Ukrainian culture’s vision to the West.

Not many people know that while director Paradzhanov filmed Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors in the Carpathians, Stus wrote heartbreaking letters to Andrii Malyshko about the total russification of Ukrainian Donbas, in Kyiv a group of musicians-sixtiers was formed – academic composers, later known as “Kyiv avantgarde.” Because of fewer cultural regulations, these people got access to global academic music and tried to make Ukrainian music closer to it.

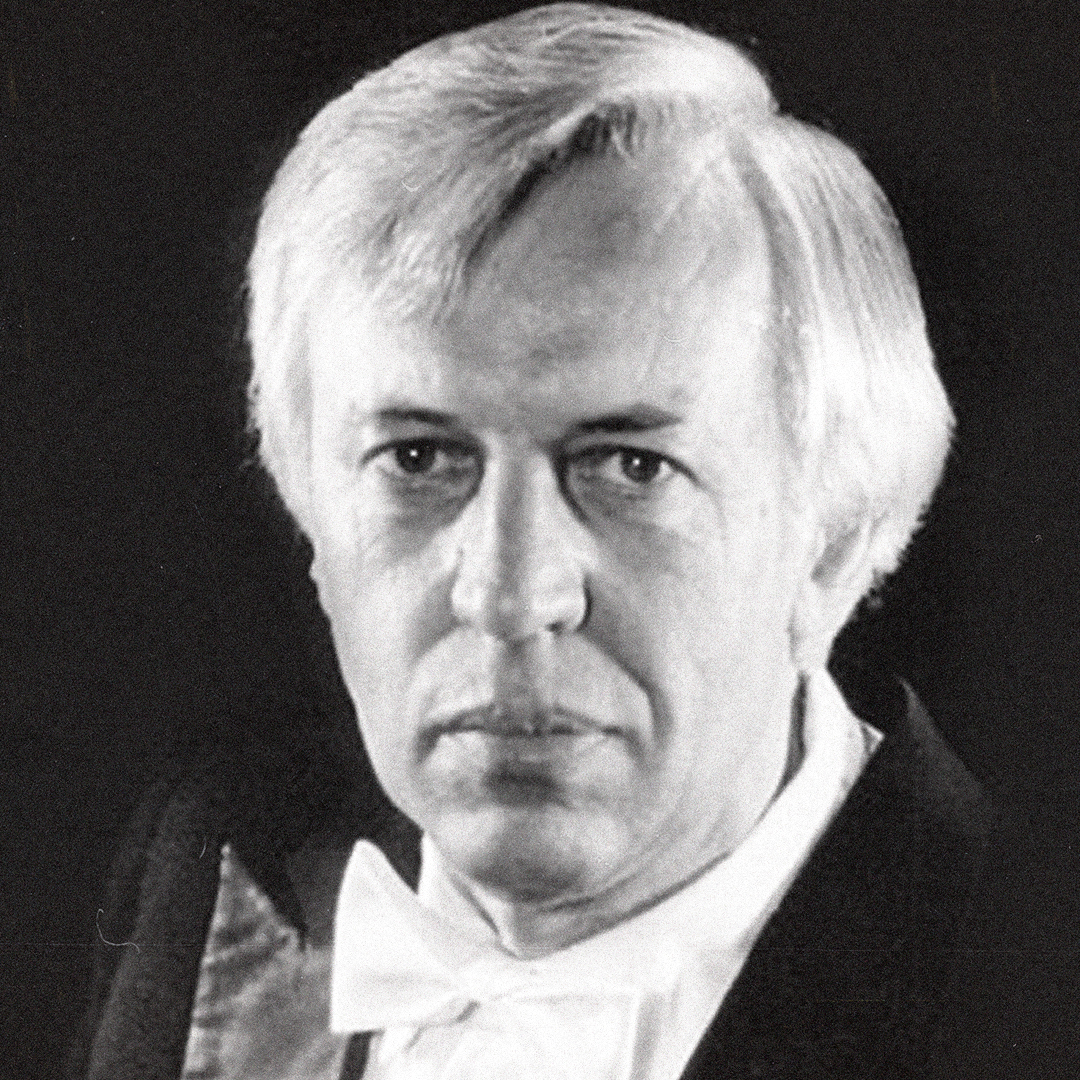

Valentyn Sylvestrov, Leonid Hrabovskyiyi, Vitalii Godziatskyi, Volodymyr Zahortsev – they are pupils of Borys Liatoshynskiy, a composer, mentor, and conductor, the founder of modernism in Ukrainian classic music. Being students of Kyiv conservatory at the beginning of the 60s, they played music of pretty much the same high quality as Polish and Russian avant-garde of the time: foreign critics assume that Kyiv composer’s school had its own unique sound.