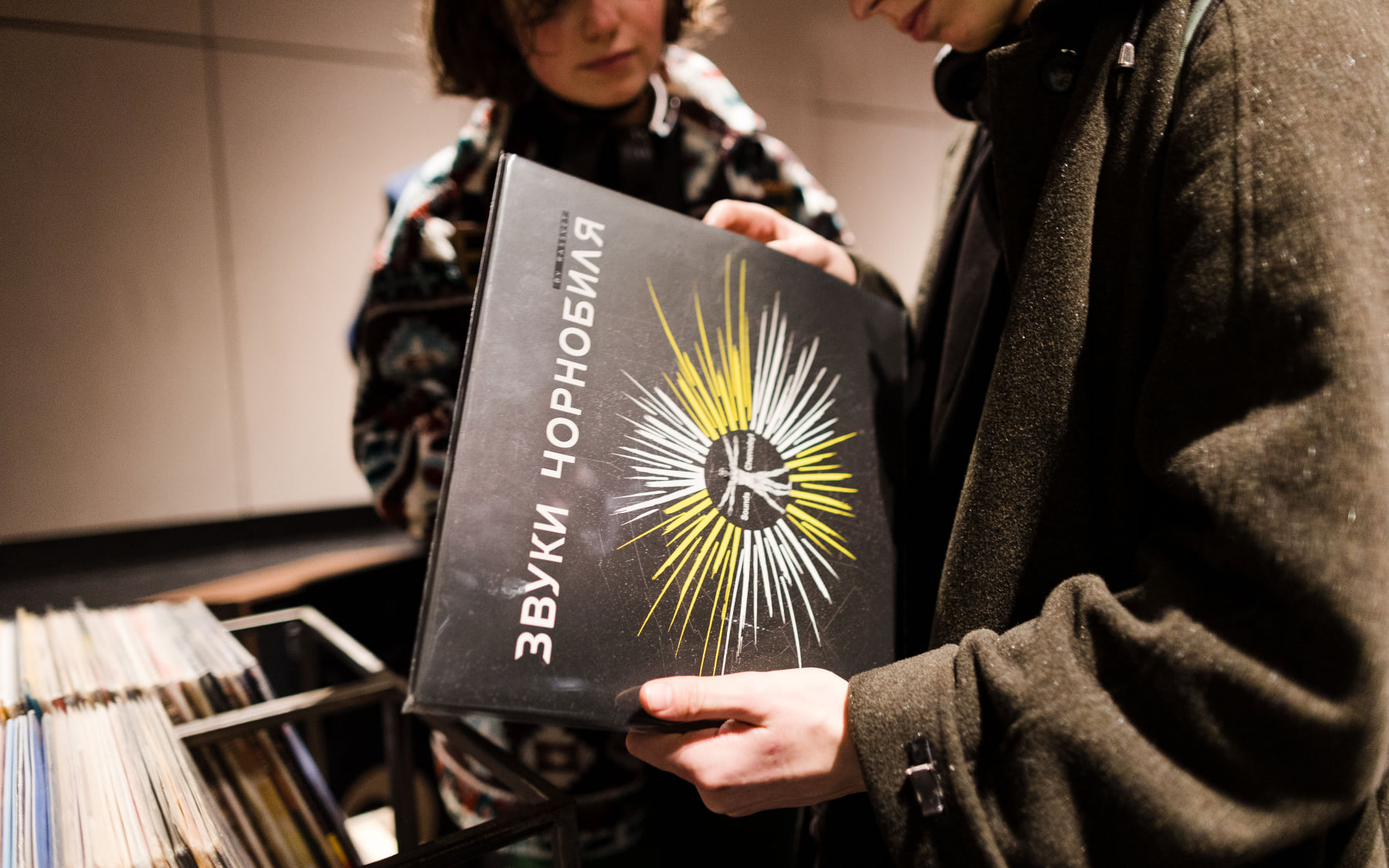

During its existence, vinyl was something sacred-a personal contact of the listener with the music, the album, and, at the same time, with the artist. Records are the kind of music you can hold in your hands, care for, wipe off dust, show friends vacation photos, and touch and feel the magic. Such an intimate ceremony took place with the participation of Ukrainian music.

The first record on which the Ukrainian language sounded was recorded in 1899 by the Emil Berliner company in London. The following year, this firm recorded seven more records with Ukrainian singing. At the beginning of the 20th century, there was already a record company, “Ekstrafon,” in Ukraine, which produced records on the spot. This is how the recordings of the choir of M. A. Nadezhdynsky appeared with the songs “Oh, the dove flew”, “Oh, the girl walked”, “Has forged the grey cuckoo”, and in 1914, for the anniversary of Shevchenko, they recorded “Roars and moans of the Dnipro wide”, “And a wide valley”, “If I had shoes”, “Fires are burning, music is playing”, “Water flows into the blue sea”.