How Moscovia Appropriated the Part-song

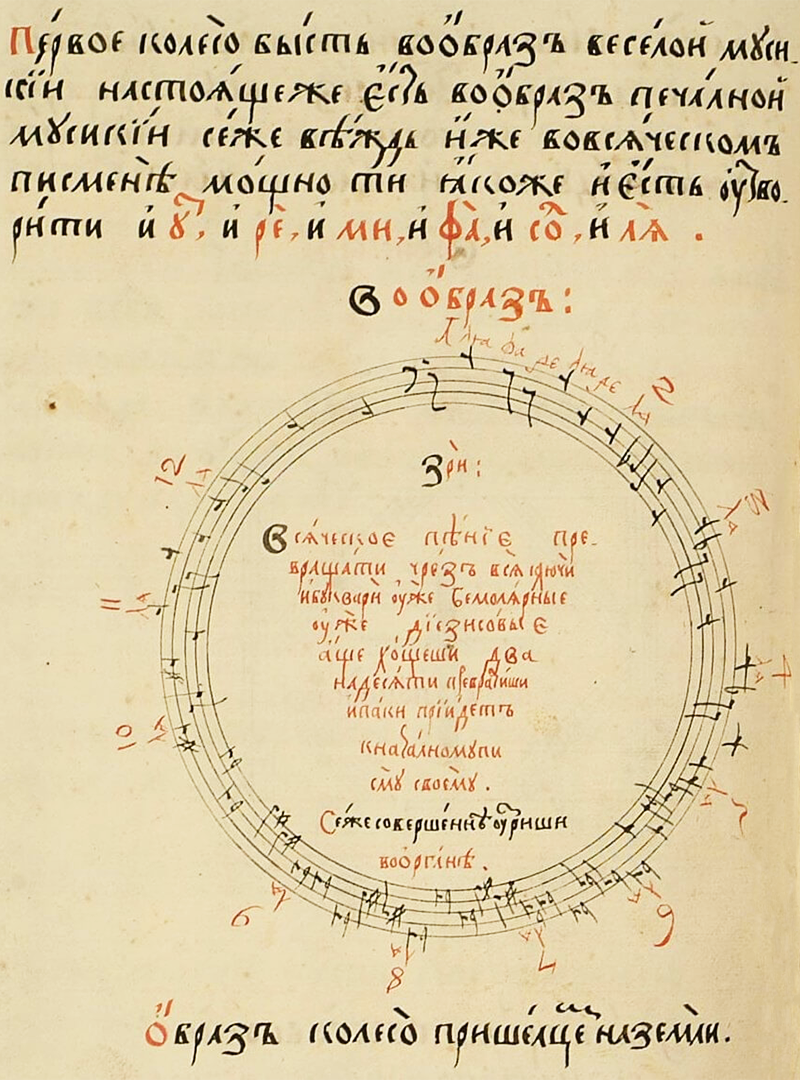

Almost nothing is known about the part-song in the early stage of its development. Most sources and artifacts are dated to the second half of the 17th century. It springs from the fact that the Pereiaslav Council took place in 1654: Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi made up his mind to unite with the Tsardom of Moscovia in the war against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. All cultural property belonging to the Ukrainians came in handy for Moscovia which had referred to Ukrainian achievements as their own already at that time. Things like this happened to the part-song too.

The part-song came from Italy, got to Poland, from Poland to Ukraine, from Ukraine to Moscovia, according to the Russian myth. How could the part-song then miss Austria and Hungary before reaching Poland? The legend does not give any reasonable answer; moreover, the whole version does not hold water.

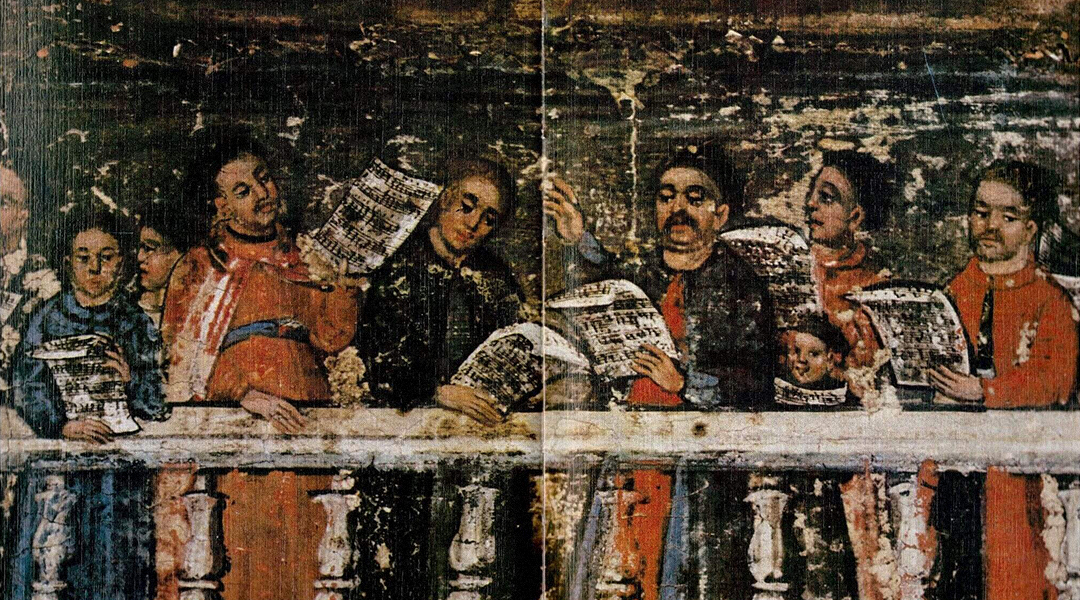

The Pereiaslav Council, so-called “merger” of the Cossack Hetmanate with the Tsardom of Moscovia, triggered a considerable part of the artistic intelligentsia from Ukraine to begin to study and work in Moscow.

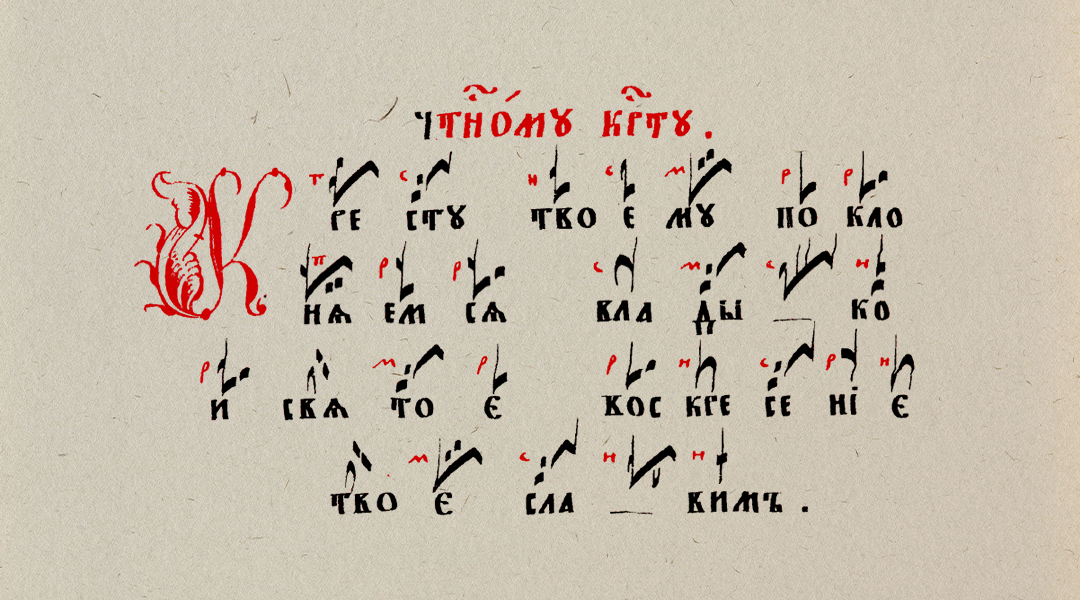

The part-song was written by such Ukrainian artists as Mykola Dyletskyi, Symeon Pekalytskyi, Ioan Domarytskyi, and a range of anonymous authors at that time. The music gaining of anonyms is the greatest part of retained artifacts of the part singing for now.