No matter how strong the Iron Curtain was, at the end of the 1960s, Western beat music still made its way to the USSR and Ukraine. For the most part, it was a simplified British version of American proto-rock and roll. The party banned it and various genres of rock, such as big beat. Therefore, Ukrainian musicians combined the sounds of the free world with folk motifs as the Soviet government gave the green light to such a symbiosis.

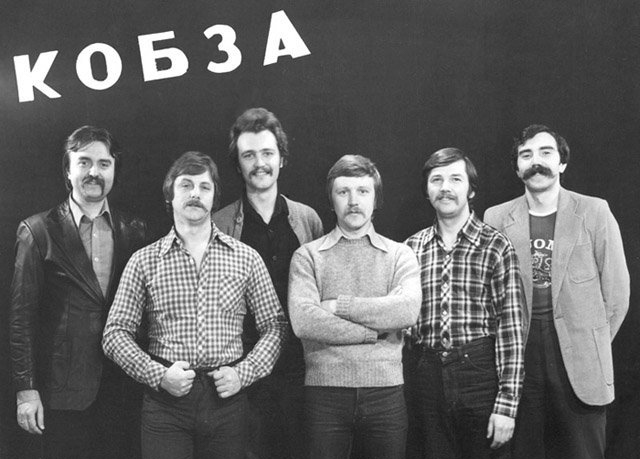

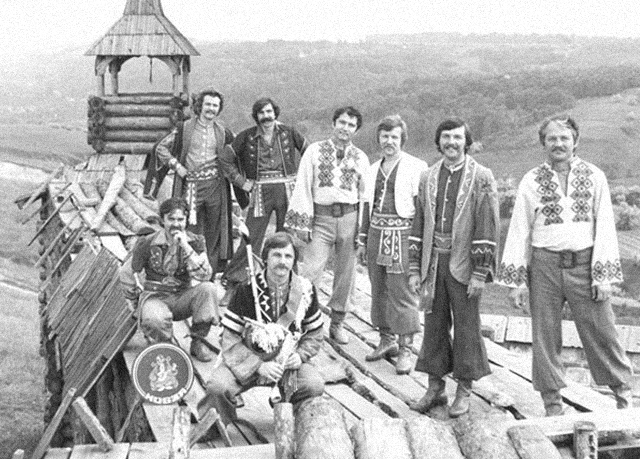

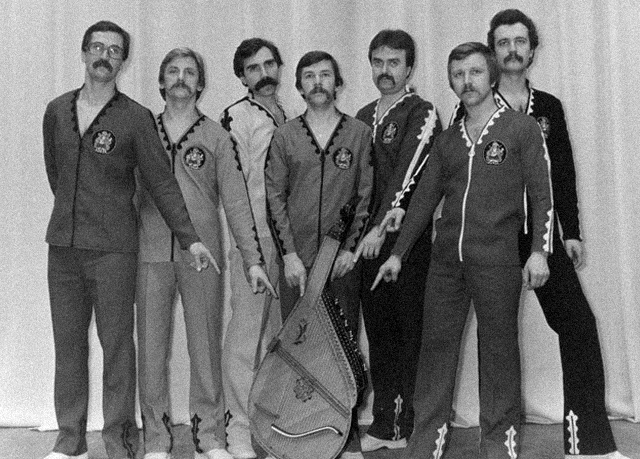

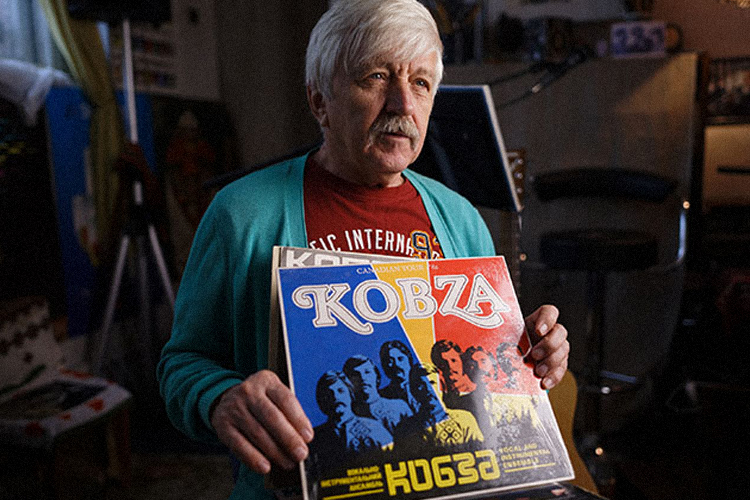

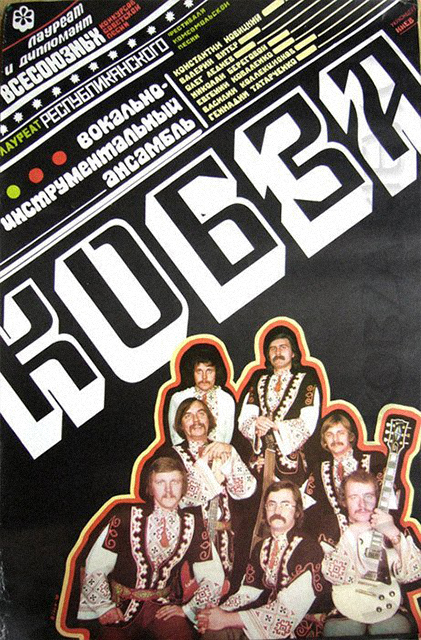

Vocal and instrumental ensembles, VIEs, have become a breath of fresh air for Ukrainian culture. One of the first folk-rock bands of such kind in Ukraine was VIE Kobza, and they were called the “Ukrainian Beatles”. They played concerts throughout the Union and abroad, and the group’s records sold millions of copies.

Read about the rock stars of the Ukrainian scene of the 70s who made progressive music and how wild success did not stop their slow fading.