For centuries, the aggressor country, russia, put a lot of effort into destroying the Ukrainian nation’s identity. The Soviet Union inflicted the biggest blow to our culture – the authorities confiscated the national assets for the good of the “great country” while banning the Ukrainian language, killing Pro-Ukrainian cultural figures, or persecuting them throughout their lives.

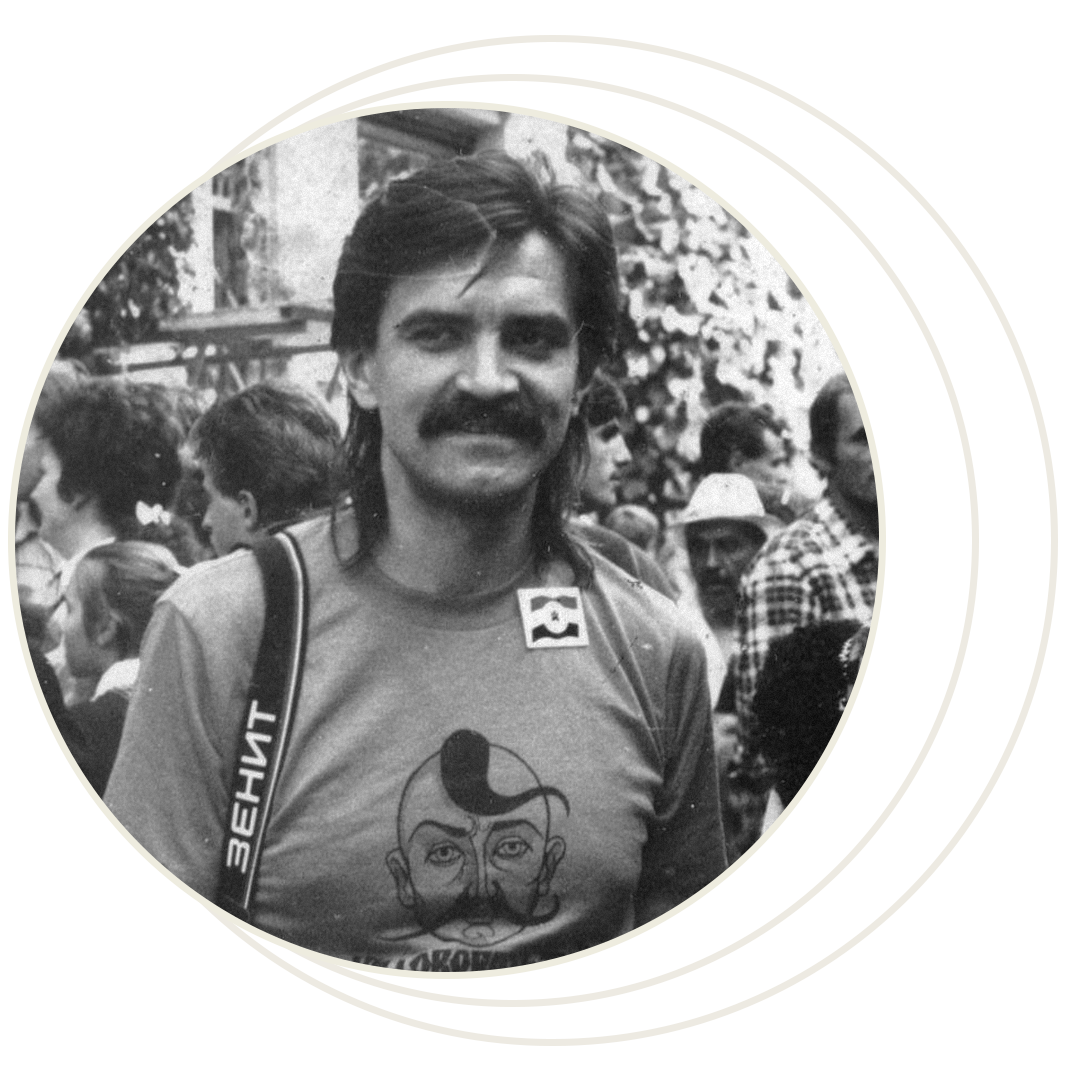

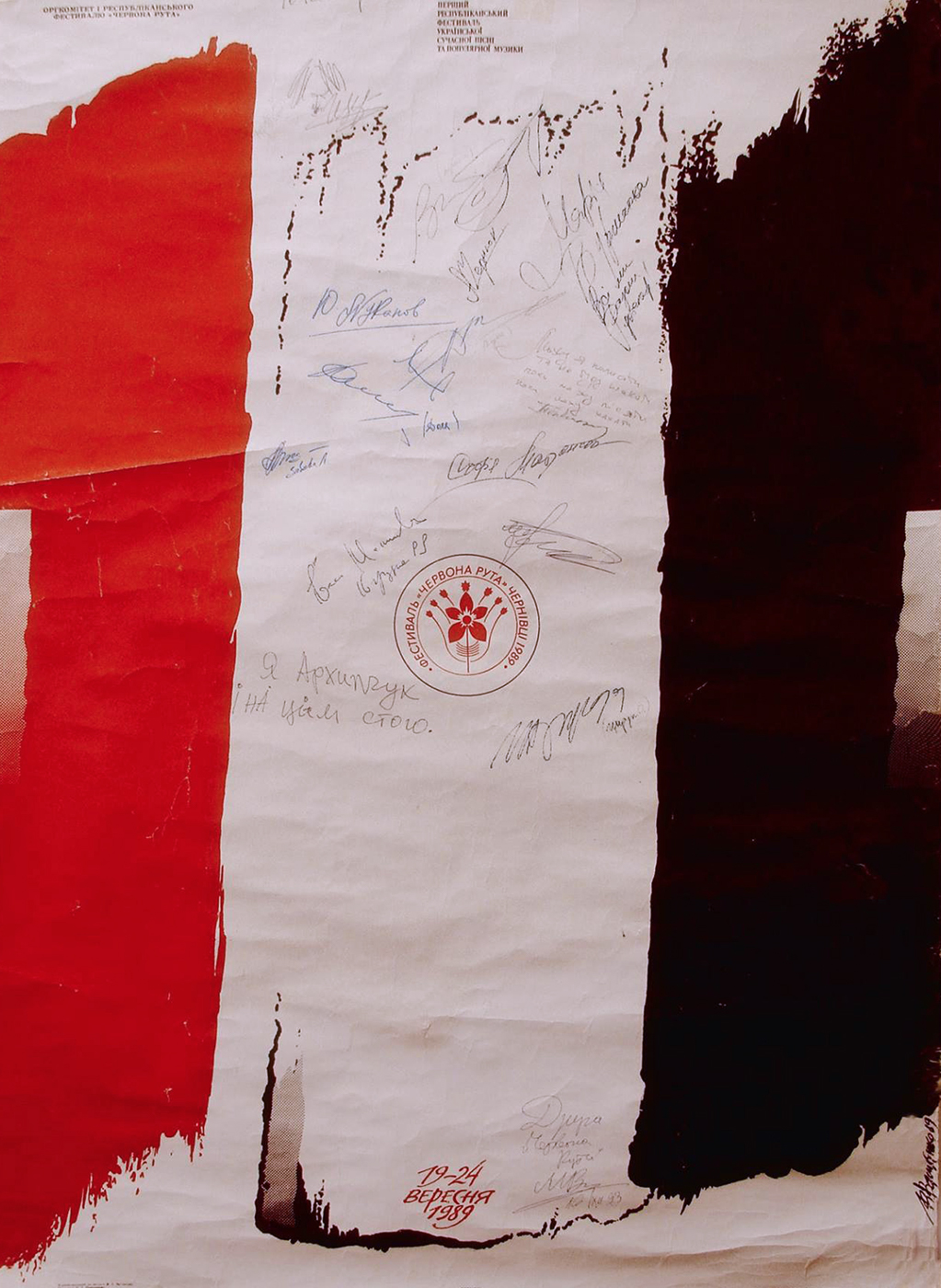

In such conditions, a cultural resistance movement was born in Ukraine, gaining its greatest strength in the 1980s. That was when the events that determined the direction of future independent Ukrainian culture development took place. Chervona Ruta-1989 festival was among them.